Dear reader, I’ve been writing more lately at Substack. It’s just proving to be a simpler, more community-oriented platform to work with. That means that those of you who have been reading me here have been left out in the cold, and I’m sorry. I’ll try to crosspost a few more things more regularly. For now, enjoy this piece on a couple of recent movies, published at Substack under the title “Of Fantasies and Tragic Flaws.”

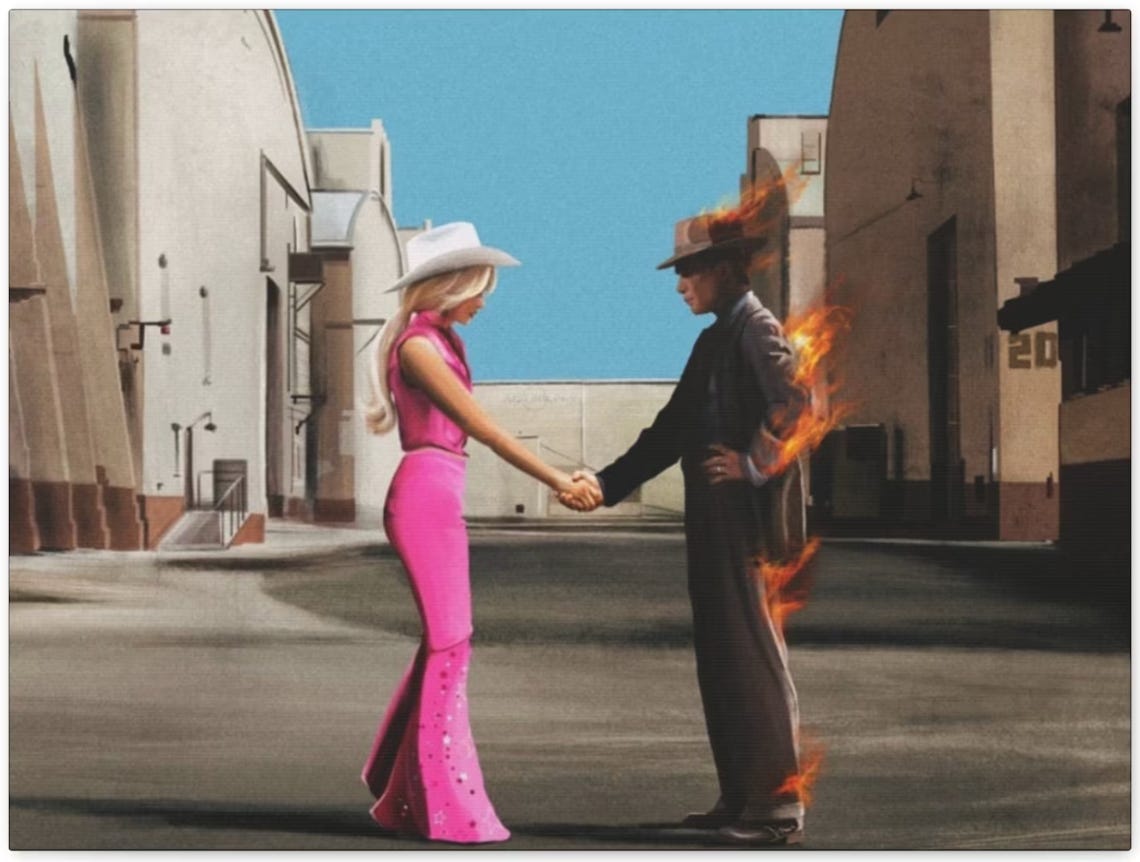

Rachel and I had the rare chance to go (kid-free) to not one but two movies this weekend. The #Barbenheimer phenomenon was too much to resist. Both films were astonishing feats of what is possible with a big-studio movie in the hands of a capable writer-director given free rein. Both drew out some incredible performances; both leaned hard into all-encompassing sets and costuming. Though very different, both are great films and worthy of going to see (give Hollywood a reminder that the universe doesn’t have to be comic book movies all the way down).

After a couple of days to reflect, I’m still somewhat surprised that, of the two films, I liked Barbie more. Yes, it was constrained to the box Mattel allowed for it, but Greta Gerwig managed to craft something cry-laugh funny and replete with pop-culture references (that felt laser-targeted to us as “elder Millennials”). It also had quite a surprisingly deep heart, if a bit didactic at times. Satire is precisely the right tool for some messages.

If you know me, you know what a history and science nerd I can be, so what I said above surprised me. I am literally the target audience for Oppenheimer. And it was 99% what I hoped it would be. I can’t remember the last time I felt so emotionally drained leaving a movie theater. Christopher Nolan’s work shines as a study of power and the machinations of power on the most epic of scales, but…

**Some spoilers for both films beyond this point!**

…I’m not sure I can forgive him for the blindspot in how he allowed his power as a prestige director in a big-budget, Oscar-bait film to put Florence Pugh in the spot he did. Power can use others, and though everyone involved may contest my interpretation, I felt like Nolan used her in ways that he should have restrained himself from (or that someone, anyone, should have tried to talk him out of).

However accurate to the facts of the Oppenheimer/Tatlock affair, Nolan went way, way over the top in how he structured her scenes (dear reader, I’d almost suggest that, before you go, you find a spoiler-filled review that explicitly details what is, um, explicitly detailed on screen). Onscreen sexual chemistry need not be portrayed through onscreen sexual exploitation.

The irony is not lost on us either that it was Gerwig who gave Pugh a star turn, using all her range to great effect as Amy in Little Women (2019). In Oppenheimer, she is little more than a set piece. Both my wife and I actively recoiled at this in the theater, and, a few days later, it’s really clouding our view of the whole film, a glaring, unforced error that mars an otherwise elegant movie. It’s all the more sad, because (at least for me), it overshadows the immense emotional heft of the film as a reminder of the demonic horror of nuclear war and the precarious balance our world still hangs in as a result of Oppenheimer’s work.

The Company of Men

Nolan’s lack of facility with female characters has long been considered a weakness of his movies. Emily Blunt’s Kitty Oppenheimer is given a rounder, more powerful role than many of Nolan’s characters, but both Blunt and Pugh’s performances weren’t given the space to show the intellectual and emotional prowess of these two women that was likely crucial to why Oppenheimer was drawn to them both. Perhaps, though, this shortcoming fits this particular story.

The worlds of the 1940s, of physics, of War, are inescapably masculine. That is, a culture which included women in more decision-making spaces would likely never have launched a Manhattan Project. And perhaps few female filmmakers would have been drawn to adapt American Prometheus. The movie, like the project it depicts, is shaped by the company of men. It is, as W.H. Auden put it, “A phallic triumph.”

That line, from Auden’s 1969 poem “The Moon Landing”, indulges in a bit of gender essentialism (yes, women, as well as men can be theoretical physicists or rocket scientists, but they might not try to do the same sorts of cosmically risky things with their powers). He pinpoints, though, the danger of closed rooms and closed conversations, saying that such ventures,

“would not have occurred to women

to think worth while, made possible onlybecause we like huddling into gangs and knowing

the exact time: yes, our sex may in fairness

hurrah the deed, although the motives

that primed it were somewhat less than [human].A grand gesture. But what does it [portend]…?

….We were always adroiter

with objects than lives, and more facile

at courage than kindness: from the momentthe first flint was flaked this landing was merely

a matter of time. But our selves, like Adam’s,

still don’t fit us exactly, modern only

in this—our lack of decorum.”

In our world, any tool eventually metamorphoses into a weapon. And within a sufficiently closed loop of institutional privilege, any person can be reduced to a tool.

Hegemony, Hierarchy, and Hope

If not for the obsessive marketing of both films and the pressure to join in the “Barbenheimer” festivities, I might not have put these two films in conversation with each other, but it’s hard not to see the world of Oppenheimer (on film, and perhaps on set) reflected in the tongue-in-cheek patriarchy of Gerwig’s “Kendom” in the second half of Barbie.

After being exposed to the Real World, Ken decides Barbieland will be better if the Kens are in charge. In such a fanciful realm, this takes the form of all the highly accomplished Barbies being brainwashed into thinking that cheering on the Kens’ useless antics and keeping them supplied with “brewski beers” is worth trading their agency and responsibility for. It also, somewhat predictably, devolves into war (after a fashion).

The restoration of Barbieland, though, doesn’t come through the triumph of radical feminism, but through empathy, honesty, healthy boundaries, and commitment to inclusion. That’s not to say that radical feminism (or, at least the still-far-too-radical notion that women are fully orbed humans) isn’t a driving force of the film, but Gerwig is smart enough to know that for men and women to flourish together, we need each other. The extent of this theme is, critic Alissa Wilkinson points out, practically a comic retelling of a certain misreading of the Genesis narrative. A world exclusively by and for one sex, where members of the other exist only for burnishing the image and reputation of their counterparts, is not an Eden, but a hell of sorts. The way out is not revolution and reversal but mutual remaking.

Sometimes cinema still dazzles, but I’ll always maintain that the best films are anything but “entertainment.”