Seeking “the meaning of life” is as human an activity as breathing, and wrestling with why things aren’t as good as they could (should?) be follows close behind. For better or for worse, I can’t stop reading books that propose to answer the pervasive sense of foreboding about the status quo that so many of us feel.

As someone who stands up in church every Sunday to confess that I believe in the resurrection of the dead and the life everlasting, this habit of watching for the end of a certain world seems a bit incongruous. I’d like to think I’m in good company with prophets (like Daniel, Ezekiel, and Micah) and apostles (like Peter and John) in looking for the Day of the Lord. They remind us that it is possible to raise up a Jeremiad with joy and to temper handwringing with hope.

So I keep reading and listening. This is true whether these works come from a political science perspective (like Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed), a sociological perspective (like Charles Murray’s Coming Apart), a religious perspective (like Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option), a personal memoir (like J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy and Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me), the agrarian (all of Wendell Berry’s work), the poetic (like W.H. Auden’s Age of Anxiety), the dystopian (like P.D. James’ Children of Men), and even the historical (like Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning). Look in any direction and it’s existential crises for days, but there’s always something to learn.

One thing all of these books have in common is an explanatory posture—they attempt to make sense of the loss and the dread and offer some semblance of a way to the good (looking back for some, forward for others, and grasping at things not yet seen for a few). Most start from a place of reminding the reader what society stands to lose if we’re not careful, a warning to the privileged that their inheritance is spending down faster than it is accruing value. Others point out that what we’ve inherited was never what we thought to begin with.

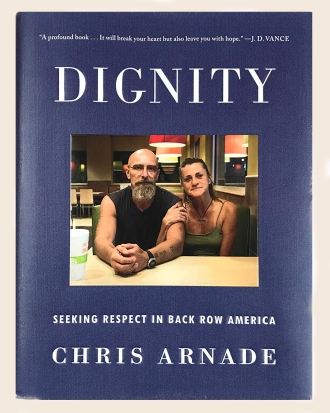

Of all the “here’s what’s gone wrong w/America” takes, however, Chris Arnade’s recent book Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America is one of the most honest I’ve seen. Though the author (a former Wall-Street banker who also holds a Ph. D. in physics from Johns Hopkins) possesses greater privilege than many others in this group of writers, Dignity takes pains to center with humility and humanness those for whom America has gone most wrong. Those who are being ground up get the focus and the voice here; those who’ve lost already, not those who merely fear what they may lose.

Some of this comes from the book’s format. It’s not an academic or even a narrative work, but rather a travelogue weaving episodes and itinerant thoughts with personal stories from all over the U.S. It’s also a sort of coffee-table book: Arnade is an accomplished photographer, and the faces and places he encounters feature prominently throughout the book, giving the words flesh and feeling.

At first, Arnade appears to be launching into memoir as he recounts the beginnings of this project in his long walks in New York, farther and farther afield from his Manhattan office. At some level, he never leaves this mode, stick ing around to narrate, to tie together disparate interviews, and to offer an epilogue of his visit back to his hometown.

ing around to narrate, to tie together disparate interviews, and to offer an epilogue of his visit back to his hometown.

His voice, though, isn’t the thing you take with you. It’s the words of Takeesha, Imani, Luther, Jeanette, Beauty, Fowisa, Jo-Jo (all street names or pseudonyms to protect their identities), and the others you meet in these pages. It’s the drugs, chemicals of every kind that can be swallowed, snorted, smoked, or shot up. It’s the emptiness of homes, factories, cities, and towns that once held a fuller life. It’s the inexplicable persistence of community in McDonald’s, churches, bars, abandoned buildings, and parks. It’s the clear-eyed pictures of racial injustice that still pervade America and the ways its evil seeps into and drives other class and culture issues.

The photos-and-snippets motif Arnade chose invites comparisons to Depression-era narrative shapers like Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. He is justly in their company in terms of his photographic eye, but his artistic aims are more subdued. He paints people not as victims in need of assistance or pawns in a political game, but as they are—human beings, broken and beautiful, navigating the life they’ve got with the tools they have. This gives the book a strikingly agenda-less quality. Yes, he addresses globalization, crony capitalism, automation, family fragmentation, drug policy and other macro-level trends that have contributed to the plight of his subjects in some way, but he shies away from any prescriptive action steps. Some may find this (and the attendant lack of concrete “solutions” to “problems”) frustrating, but I think it is a critical posture for the observations Arnade makes to be taken seriously.

Throughout the book, he presents the key divide in American society as that between the “front row” (educated, workaholic, powerful, cosmopolitan, upwardly mobile, rootless) and the “back row” (underemployed, powerless, bound to place, loyal, struggling). Arnade uses these terms descriptively, but neither is intended derisively—front row and back row America both have values and vices, but their cultural currencies and drugs of choice differ widely. Both can provide meaning and community, but both battle despair and can be toxic to outsiders.

It is in the question of values—or rather value—where Arnade makes his most helpful contribution to our national conversation. The front row, he says, lives by “credentialed” value. A person is welcomed into that community based on their gifts and abilities, their degrees, their accomplishments, and their contributions to others’ well-being and success. This world is competitive and rewarding, but also insecure. In the back row, value is “non-credentialed.” Your identity and worth comes from things you are born with (family, ethnicity, work-ethic, local roots) or from belonging to groups that are accessible to almost anyone willing to join (a church, a drug community, a gang, becoming a parent).

At present, the high places of cultural influence and power are open only to the front row, and the non-credentialed bona fides of the back row aren’t likely to earn you a seat at the table or a steady job. If there is an ax to grind here, it is Arnade’s persistent message to his fellow front-row-ites that the meritocracy at the helm of American society today is a much, much more closed system than they’d like to believe. His forays into the back row—whether in Bakersfield, Calif., Johnson City, Tenn., Selma, Ala., Portsmouth, Ohio, or even neighborhoods of front-row cities like New York—demonstrate how the solutions of the front row (“get an education,” “move away,” “get clean,” “learn new skills,” etc.) are much higher mountains to climb from this different perspective. What seems like common sense to one group is to another group a command to turn one’s back on everything they’ve ever known. The repetition of this theme comes both from his desire to make this known, but also because his interviewees so frequently have been confronted by this stark divide.

Dignity matters, not as another explainer of “how we got Trump” or a push for better government and nonprofit programs for poverty alleviation (though it has implications for those discussions), but as a step toward helping us as a country see all of our neighbors as brothers and sisters. Arnade does not claim to be a Christian, but he is implicitly calling us to recover the imago dei as the final arbiter of one another’s value.

Arnade’s lack of professed faith also makes his assessment of the real value of congregational life and earnest beliefs in the churches (and mosques) of the back row that much more remarkable. In an excerpt from the book published in First Things, he writes: “My biases were limiting a deeper understanding: that perhaps religion was right, or at least as right as anything could be…. On the streets, few can delude themselves into thinking they have it under control. You cannot ignore death there, and you cannot ignore human fallibility. It is easier to see that everyone is a sinner, everyone is fallible, and everyone is mortal. It is easier to see that there are things just too deep, too important, or too great for us to know.”

His chapter on religion hit closest to home for me and the work that I do. The churches he visited in the back row certainly don’t check all the theological or cultural boxes front row Christians deem necessary, but they all reflect the person of Jesus Christ in loving their neighbors and being faithfully present with them. Too often, front-row Christianity (whether conservative or liberal in theology, whether high-church or low-church in polity) has trouble doing this—we’re not quite sure what we’d do if someone from the cultural back row walked in and wanted to join. We don’t often have a story of change that would work for them. Doctrine, expected behaviors, and appropriate political positions we can get our minds around; Jesus gives us heartburn.

So where do we go from here? How do we build up? As I said, Dignity is long on observation and short on solutions. Many others are starting to digest the realities on the ground and work toward tying some of these threads together in ways that can repair the breach and bring people back to the wholeness we were designed to experience together. I’ve highlighted some of these on Twitter (that paragon of civil discourse), and in other writings, and I’m sure it’s a theme I’ll take up again. Moreover, this is no small part of the mission of the ministry where I work.

For now, though, let Dignity soak in and open your heart to those you might otherwise be tempted to forget.

Image: Abandoned farm equipment, Channel Islands National Park, California, June 2019